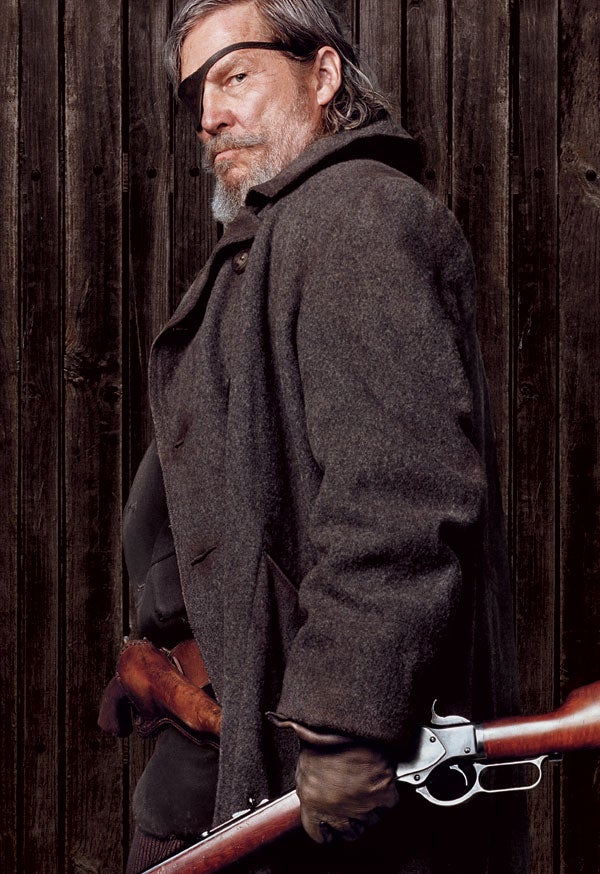

Tom Sutcliffe: Rooster's a bit too slow on the drawl

The week in culture

It's something of an irony that, in most commentators' predictions, Colin Firth is squaring up against Jeff Bridges for the Best Actor Oscar. On one hand, you have a character for whom clarity of speech is a dream, involving a lifelong struggle against inherited impediment. On the other, you have a character who has no physical problems in speaking at all, but most of whose utterances are completely incomprehensible. In fact, somebody has already made an effective joke out of the startling muddiness of Rooster Cogburn's speech, posting a doctored montage of clips from True Grit on the internet, running its own surreal guesses at what's being said underneath on subtitles. And with that performance Jeff Bridges – always a mutterer of talent – has definitively sealed his place in the Cinema Mumblers' Hall of Fame.

He's in reasonably good company. Marlon Brando is certainly in there, both for his ground-breaking muttering in the first Godfather movie – (where the muffling was partly down to the heavy cotton-wool padding he'd stuffed in his cheeks to fill out Don Corleone's jowls) – but also for his winningly incomprehensible growls as Kurtz, at the end of Apocalypse Now. Sylvester Stallone has a place – for diction on and off screen – and Heath Ledger too, not a career mumbler in truth but given an honorary position thanks to the shit-kicking drawl he employed in Brokeback Mountain (which occasionally made you wonder whether Jack turned to sex up in the mountains because conversation with Ennis was never going to be a viable alternative). And I think there might be a special mention for Brad Pitt's role in Guy Ritchie's Snatch, though purists might object that comedy incomprehensibility (Pitt played a pugnacious Traveller with an accent so dense only one word in 10 got through) doesn't really count.

A friend who saw True Grit suggested that Bridges's mutter was a fruitless attempt to naturalise the over-literary nature of the Coen brothers' script. He looked at those bookish lines, with their ornately formal diction, and thought "How the hell am I going to make this sound real?" And his solution followed a path well trodden by other American actors before him, who identified rough edges and unprojected speech as the hallmark of life. I'm not so sure. I think Bridges was perfectly happy with the script and even enjoyed its grace notes. He just thought that Rooster would probably talk something like this – a man who doesn't much care whether other people can understand him or not, because he makes most of his points with a gun. But one thing you can say for sure is that 60 years ago his delivery would have been regarded as something close to a catastrophe for a movie – the kind of thing that would have had a studio boss ordering him back into a dubbing studio at once.

These days, of course, it's a badge of realism, and, perhaps emboldened by subtitled DVDs and the opportunity to re-run a scene until you can finally make out what a character's saying, directors and actors employ it pretty widely. Like most of cinema's badges of realism though it isn't actually very realistic. When did you ever, for example, see a character on-screen say, "Sorry, I didn't quite catch that. You're really going to have to speak a little more clearly." That's what would happen in real life if someone genuinely talked like this, but, unless the plot specifically requires a misunderstanding, the characters of movies inhabit a space of ideal communication in which meaning is never mislaid, however smeary the diction. Our exclusion from this space is part of the trick – the sense that our comprehension isn't an issue because we're not really there. If there was an audience they would project a little more clearly, obviously, but since there isn't they don't have to. And the ignoble thought occurs that there might actually be some performers hiding out in the verbal undergrowth here, knowing full well that the fine details of their performance may not be visible at all. Colin Firth – articulating every syllable including the stammered ones – puts every nuance on display so that we can judge it. Jeff Bridges delivers a kind of auditory impasto that effectively makes fine judgement of nuance impossible. They're both fine performances, but I hope the old-fashioned "unrealistic" one gets the prize.

It's always wise to tuck into a second helping

I saw an interesting tweet the other day: "How good is the Friends pilot? So good that you know 4 characters after SEVEN LINES". It was originally posted by Andrew Ellard, a script editor for The IT Crowd and he helpfully attached a link (http://t.co/ACfSYxE), so that anyone interested could check it out. And if you look you can see exactly what he means. It's really tight writing, and, looking back in hindsight, every line is comically typical of its speaker. But I'm not sure that Ellard has quite taken hindsight into account – or at least the fact that comedies often depend on us knowing what is typical of its characters in order to make a line funny. It's one reason why even the best written pilot always labours uphill, because its main job is to clarify the outline of a type or personality that later episodes can have fun filling in. And it's why no critic should ever categorically dismiss a new comedy before seeing at least three episodes. This was underlined for me the other night when I watched the first two episodes of Friday Night Dinner, Robert Popper's new sitcom for Channel Four. First episode? Well... meh, really. Nicely acted comedy of awkwardness and family in-jokes, but a little underwhelming. Second episode? Very funny indeed, I thought – because you can predict roughly how the characters will react, but not what specific form their reactions will take. And I bet the first episode will look funnier next time I look.

Isabella explores basic instincts

The Natural History Museum's new exhibition, Sexual Nature, is something of a mish-mash, a cabinet of curiosities assembled around the fantastical varieties of animal sexual experience, which includes detachable penises designed to block the advances of love rivals and bifurcated vaginas, with which female ducks can bamboozle the sperm of unwanted mates. On display are penis bones and jarred specimens of beasts with outlandish mating habits. Easily the best thing though, to my mind, was Green Porno, the name actor Isabella Rossellini has given to a series of short films in which she acts out the mating behaviour of various animals, with the help of brightly coloured sets and paper costumes. The one devoted to the mating habits of the duck is particularly lubricious, offering a penis-eye view of the inner chambers of the duck, but there's also an excellent film in which she outlines the hazardous congress of a spider, which has to creep up on the female and insert his sperm covered palps without getting eaten. And one in which the sado-masochistic practices of snails are given wild vocal expression by Rossellini herself. I'm not sure that their shameless anthro-pomorphism makes suitable viewing for a scientific institution, but they're available on YouTube if you fancy a bit of bestial action.

t.sutcliffe@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments