Turner Prize 2011, Baltic, Gateshead

It's never easy to predict, not least because the best artist so seldom wins. But this year's Prize is hard to call because the shortlist is so strong

This year's is the 28th annual Turner Prize show, to which you might reasonably say: so what? There have been enough of them now to know that they don't mean much.

Turner prizewinners haven't always thrived. (Where is Grenville Davey now? Come to that, who is Grenville Davey?) The big cheque has seldom gone to the best artist – I refer you to Mike Nelson and Tacita Dean – and shortlists have had a habit of being predictable, the artworld's equivalent of Buggins's turn. Worst, the Turner has favoured a certain kind of art, the sort that hogs headlines, looks good on tele-vision. Such is its power – now, thankfully, diminished – that it has pushed a generation of British artists in a single direction, pressing them to make work that catches the Turner eye; not always distinguishable from that of the Tate.

So perhaps it is that this year's Turner show is away from Tate's Millbank HQ that makes it seem less doctrinaire than usual; better, in fact. The Baltic in Gateshead has had its ups and downs, but the Turner looks happier there than it ever has in the tomb-like Tate Britain. Of course, the Tate is still behind the prize, but you wouldn't necessarily guess it. I can't recall a stronger show over the past 27 years, better chosen, better displayed, more poised or grown-up.

The problem, unusually, will be who to eliminate. Of the four short-listees, the first to go must, with a heavy heart, be Hilary Lloyd. This is not because Lloyd is a weak contender, just that the remaining three are so strong. She suffers, in this context, from making work that other people make – video installations which are also sculpture, their screens and projectors defining the spaces around them. Thus Floor is a triptych of three projections, jiggling, allusive and somehow rude. But it is also a wall of projectors, hung from the ceiling on metal units; and beyond that again, it is the tangle of flexes and adaptors that powers these things, a fringe of grunge to the glitz of film. Lloyd's work is handsome, clever, well made; but also faintly familiar, which is not a good thing in this year's Turner.

My next-longest odds would be on Martin Boyce, a good artist not at his best here. Like Lloyd's, Boyce's installation is both in the room and of it. Where the other contenders had the Baltic's iron columns covered up, Boyce has worked with them. They seem to exist for the sole purpose of holding up his ceiling-piece – a grid of white fins that feels perversely natural, like clouds or a steel tree canopy. This in turn appears to have shed the crêpe-paper leaves of his floor work. The look is theatrical, like the set for a brutalist production of The Cherry Orchard. The drama is played out by Boyce's free-standing sculptures, the most notable being Do Words Have Voices – a Calder-ish mobile made immobile by what looks like an anatomist's table. My one fear in all this is that the fortysomething Scot has tried to do too much for the Turner, that his playing-off of assemblage and artwork turns into a battle. We'll see.

I'd love it if George Shaw won, though I doubt he will. The trouble here is that Shaw's paintings are the opposite of attention-grabbing, being, on the face of it, archaically skilful. They are landscapes and cityscapes, although, being modern, they are not picturesque. Very much not: the scenes Shaw depicts are of a grungy 1950s housing estate in Coventry, the setting of his own childhood.

That is nothing new, either: the bringing of high-art techniques to low-art subjects is a favourite Postmodern game. That Shaw paints in Humbrol colours – the ones used for model aeroplanes – might also be put down to a bit of conceptual playing around, ironic nostalgia. Except that the result doesn't feel like that: it feels both new and – shock! – sincere. The sheen of Shaw's paint glazes his surface, so that we are actually looking at the deadening places he paints; a déja vu we didn't want to see, even once.

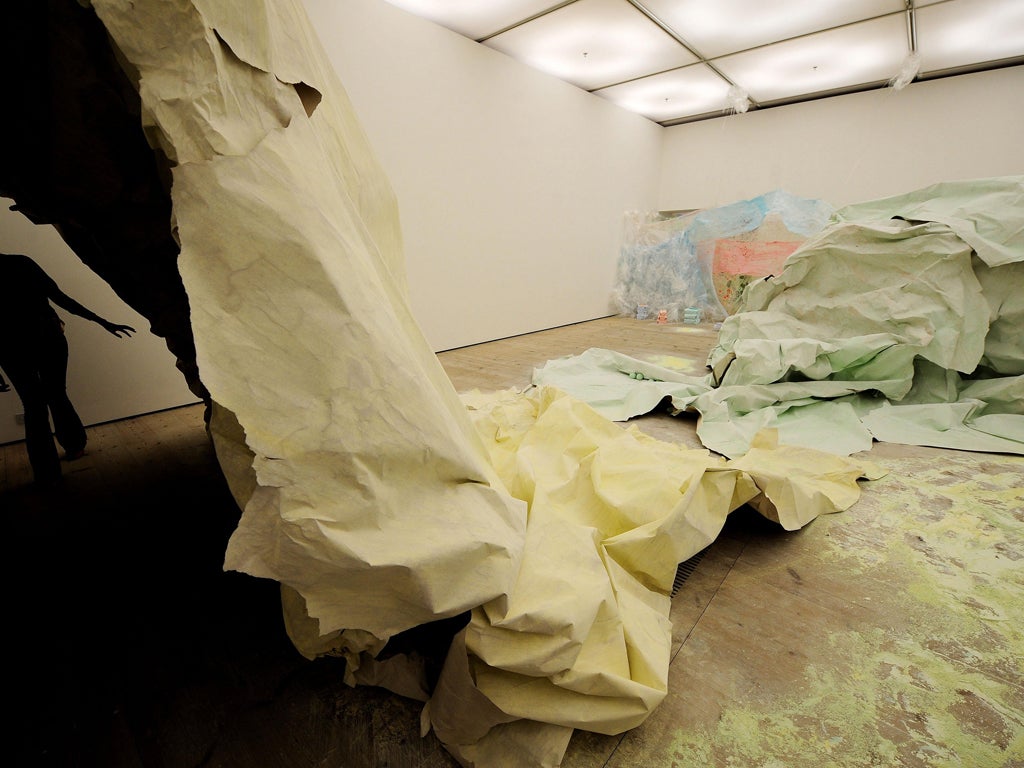

And so, to Karla Black. It is difficult to say why Black is such a great artist, and that's a good thing. Too much contemporary art sets out to be put into words. Black's room-sized Turner installation is actually two pieces, although that need not detain us. As ever, it works with colour and texture and something more – the allusive power of ordinary things, maybe. Here, as at the Venice Biennale, Black sets up a sense of the familiar unknown. Her vast construction of crumpled sugar paper and cellophane calls up all kinds of ghosts: sweetie-wrappers and pastel soap, old ladies' face powder. These things are gentle, fragile even. And yet what Black makes of them is monumental, perhaps even heroic. Of course my money's on her, so of course she won't win. There goes another tenner.

To 8 Jan (0191-478 1810)

Next Week:

Charles Darwent follows the money, and the link between cash and patronage in Paris and in Florence

Art Choice:

Tacita Dean has taken on Tate Modern's Turbine Hall; her 11-minuteinstallation, FILM, will be lighting up the space until 11 March. Andy Warhol's philosophy, work, lifestyle, and legacy for the 21st century are examined in a Tate Artists Rooms' show at the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, East Sussex (to 26 Feb).

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies